by Niall McArdle

Top Ten Tuesday is a bookish meme started by The Broke and the Bookish

John Banville is going to win the Nobel Prize for Literature sooner or later: maybe even this year. He has won the Kafka Prize, and in the last few months has been awarded the the Prince of Asturias Award and has been made a chevalier in the Ordre des Arts et Lettres

Top Ten Books I Would Give To Someone Who’s Never Read John Banville.

I wanted to include his novels about two great scientific minds, Dr. Copernicus and Kepler, and certainly I would recommend them. They probably deserve to be in the Top Ten; perhaps nos. 5, 4 and 3 should be thought of as one book so as to make room for them. I haven`t included his latest, Ancient Light, or his last Benjamin Black book, The Black-Eyed Blonde, only because I haven`t read them.

Banville can seem a daunting and off-putting figure for some. He is a master craftsman who writes shimmering prose, but his protagonists are the sorts that you would probably wish to avoid in real life: self-obsessed, self-deluded, duplicitous and amoral men with shameful secrets to hide. They stumble around his novels in a haze, and are generally undone by all the little things in the world, the bland ordinariness of life seems too much for them: Banville has probably exhausted every synonym for `baffled`.

Some spoilers, but you don’t really read Banville for the plot.

10. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Banville has been called ‘the heir to Nabokov’ so many times, it’s almost impossible not to find a reference to the Russian master in any discussion of the Irish writer, and Banville has written of the influence on his style. They share a fondness for wordplay, a fastidious wit, and both are prone to urgent confessionals by snobbish and amoral types.

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

She was Lo, plain Lo in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.

9: Possessed of a Past: A John Banville Reader

Contains a broad selection of his work, including some early pieces which have never been published. A very good overview of his writing.

Banville has said that Mefisto marked a shift in his writing style. It’s a short book, a meditation on numbers and chance, drugs and desire, and a remarkable take on the Faustian legend: in Mefisto we meet the foxy Felix, a character who appears again in Ghosts.

Have I mentioned the buses? I liked them, the way they trundled through the streets, gasping and shuddering, like big, serious, labouring animals. I would board one at random and ride to the end of the line, hunched in the front seat upstairs, watching the city unfurl around me, the tree-lined avenues and the little parks, the domes and turrets and curlicued facades. A hoarding would slide past, then a burnished stretch of river, then a dead-end street with parked cars and children playing ball under a rusted railway bridge.

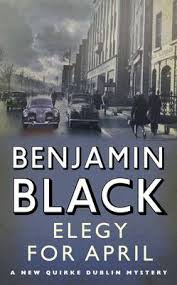

Under the pseudonym Benjamin Black, Banville has dipped into the crime genre. This is not a literary giant slumming in genre work for an easy pay cheque: his Black books are no less well-written than his Banville books. He started doing it after reading some Georges Simenon novels, and he did it to amuse himself more than anything else. Soon he discovered that his Black books came much quicker than his Banville books, and several critics are worried that Black is taking over Banville. Last year he wrote a new, well-received Philip Marlowe mystery. He has written six novels set in bleak 1950s Dublin featuring Quirke, the glum pathologist who has the habit of digging around where he’s not wanted and upsetting the status quo, tightly controlled by the city’s political and religious elite. Three of the books were filmed for the BBC, starring Gabriel Byrne. Elegy for April is the third Quirke book and for my money the best of the series.

In the Russell Hotel as always a mysterious quiet reigned. Quirke liked it here, liked the stuffy, padded feel of the place, the air that seemed not to have been stirred for generations, the blandishing way the carpets deadened his footsteps, and most of all, the somehow pubic texture of the flocked wallpaper when his fingers brushed against it accidentally. Before he had gone on his latest drinking bout , when he was supposed not to be taking alcohol in any form, he used to take Phoebe to dinner here on Tuesday nights and share a bottle of wine with her, his only tipple of the week. Now, in trepidation, he was going to see if he could take a glass or two of claret again without wanting more. He tried to tell himself he was here solely in the spirit of research, but that fizzing sensation under his breastbone was all too familiar. He wanted a drink, and he was going to have one.

For writer Colum McCann this is Banville’s warmest, most human book, a book “that breathes with humour and shines with a lovely discursive wink.” It is a charming, funny, wry tale of Midsummer’s Day at the countryside home of the Godley family, where old Adam Godley, a renowned scientist who has proved the existence of an infinity of parallel universes, lies dying surrounded by his family. There, too, is the messenger god Hermes, who narrates the novel, and who is in happy thrall to the goings-on of the humans: their loving and fighting, their sadness and despair. My full review of it is here.

This love, this mortal love, is of their own making, the thing we did not intend, foresee or sanction. How then should it not fascinate us? We gave them that irresistible compulsion in the loins – Eros and Ananke working hand in hand – only so that they might overcome their disgust of each other’s flesh and join willingly, more than willingly, in the act of procreation, for having started them up we were loath to let them die out, they being our handiwork, after all, for better or, as so often, for worse. But lo! see what they made of this mess of frottage. It is as if a fractious child had been handed a few timber shavings and a bucket of mud to keep him quiet only for him promptly to erect a cathedral, complete with baptistry, steeple, weathercock and all. Within the precincts of this consecrated house they afford each other sanctuary, excuse each other their failings, their sweats and smells, their lies and subterfuges, above all their ineradicable self-obsession. This is what baffles us, how they wriggled out of our grasp and somehow became free to forgive each other for all that they are not.

Short-listed for the Booker, The Book of Evidence is the confession by a highly unreliable narrator, aristocratic mathematician Freddie Montgomery, who stole a painting and killed a girl. Written, as Don deLillo says, in “dangerous, clear-running prose”, this is an exquisite book about a dreadful act. There are passages here that will take your breath away, and sentences so artfully constructed that you will want to stop, go back and savour them again. Based in part on a real-life Irish murder case that had a very interesting political denouement.

It was not just the drink, though, that was making me happy, but the tenderness of things, the simple goodness of the world. This sunset, for instance, how lavishly it was laid on, the clouds, the light on the sea, that heartbreaking, blue-green distance, laid on, all of it, as if to console some lost suffering wayfarer. I have never really got used to being on this earth. Somethings I think our presence here is due to a cosmic blunder, that we were meant for another planet altogether, with other arrangements, and other laws, and other, grimmer skies. I try to imagine it, our true place, off on the far side of the galaxy, whirling and whirling. And the ones who were meant for here, are they out there, baffled and homesick, like us? No, they would have become extinct long ago. How could they survive, these gentle earthlings, in a world that was meant to contain us?

Ghosts

Banville did not set out to write a sequel to The Book of Evidence, but gradually it became clear to him that the narrator of this novel was Freddie Montgomery, and it’s just as well, for in Ghosts Freddie has a chance to redeem himself (in a sense), and make good on his promise to give an imaginary life back to the girl he killed in The Book of Evidence. Freddie has served his time in prison and is now living on a remote island, where he is assisting an art historian, Professor Kreutznaer with his research into a painting, Le Monde D’Or, when a ragtag group of people – including Mefisto‘s Felix, as mischievous as ever – disembarks from a stranded boat and disrupts everything. Or are they there at all? Is Freddie in fact alone? Has he conjured Felix, the Professor, the lot of them? Has he imagined the entire golden world in this solipsistic reimagining of The Tempest – and if he has, who is he more like, Prospero the magician or Caliban the savage?

Twice a week I report to Sergeant Toner, the island’s only civic guard, a taciturn and stately figure. His dayroom in the barracks reminds me of strangely of the schoolrooms of my childhood: the dusty floorboards, the inky smell, the woodframed clock up on the wall ticking away the slow, sunstruck afternoons. Sergeant Toner moves with vast deliberation, rising from his desk in a rolling motion, as if he were shouldering great soft weights, nodding to me in sober salutation.

3. Athena

Yet another sequel of sorts to The Book of Evidence. In Athena (also short-listed for the Booker), Freddie is back in the city under an assumed name and gets caught up with some crooks who need him to pass off forged paintings as the real thing. He is also enraptured with “A”, a mysterious beauty with whom he has a passionate affair, and whose appearance and disappearance from his life coincides with a series of gruesome murders. The novel has some wonderful moments and is both tragic and rather funny in places. It also foreshadows Banville’s concern with fakes and duplicity, which he would explore in The Untouchable and Shroud, it is also a meditation on the creation of Art. Scenes in the novel are replicated in paintings supposedly by Dutch masters: Johann Livelb, L. van Hobelijn, J. van Hollbein. The names of the painters are in fact anagrams or transliterations of “John Banville”. Banville was mystified the novel was not better received: ‘I gave them sex. I gave them violence. What more do they want?’

What affects me most strongly and most immediately in a work of art is the quality of its silence. This silence is more than an absence of sound, it is an active force, expressive and coercive. The silence that a painting radiates becomes a kind of aura enfolding both the work itself and the viewer as in a colour-field … what struck me first of all was not colour or form or the sense of movement they suggested but the way each one suddenly amplified the quiet. Soon the room was athrob with their mute eloquence.

2. The Sea

The novel that finally won the Booker for Banville. At the ceremony he ruffled feathers when he said “how nice to see a work of art recognised.“ It has a startling conceit, being a memory novel that is both a coming-of-age story as well as a meditation on old age and death: the narrator is a grief-stricken widower who has returned to the seaside village where he spent summers as a child, and where a horrific tragedy occurred.

The novel that finally won the Booker for Banville. At the ceremony he ruffled feathers when he said “how nice to see a work of art recognised.“ It has a startling conceit, being a memory novel that is both a coming-of-age story as well as a meditation on old age and death: the narrator is a grief-stricken widower who has returned to the seaside village where he spent summers as a child, and where a horrific tragedy occurred.

I was thinking of Anna. I make myself think of her, I do it as an exercise. She is lodged in me like a knife and yet I am beginning to forget her. Already the image of her that I hold in my head is fraying, bits of pigments, flakes of gold leaf, are chipping off. Will the entire canvas be empty one day? I have come to realise how little I knew her, I mean how shallowly I knew her, how ineptly. I do not blame myself for this. Perhaps I should. Was I too lazy, too inattentive, too self-absorbed? Yes, all of those things, and yet I cannot think it is a matter of blame, this forgetting, this not-having-known. I fancy, rather, that I expected too much, in the way of knowing. I know so little of myself, how should I think to know another?

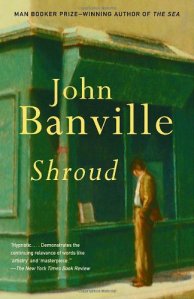

1. Shroud

After the death of the father of Deconstruction, Paul de Man, it was revealed that during the war he had written some anti-Semitic tracts. His ardent supporters tied themselves in knots trying to explain that in fact what seemed like anti-Semitic and Fascist views were in fact the direct opposite; that there was a hidden meaning in his vitriol that had to be, well, deconstructed. Banville took that instance of public disgrace and fashioned Shroud, the story of an old, famous academic, Axel Vander, and Cass Cleave, the young woman who has discovered the truth of a terrible secret about Vander’s life: that his whole life is in fact a fake. They meet in Turin, home of the famous Shroud, the most famous fake in the world. Turin is also where Nietzsche – who declared objective truth to be questionable – roamed in his final, crazed days. Again, there is an unreliable narrator, an amoral, randy old goat who drinks too much, but there is also the character of Cass, a damaged, mentally unstable woman who, like Cassandra, is powerless to stop the events she sets in motion (she has a connection to two other Banville works: she is the daughter of Alexander Cleave, the narrator of Eclipse and Ancient Light). There is dark humour and fantastic attention to detail (I can think of very few writers who can describe so well the way things smell). A book about identity, duplicity, truth and the ‘self’, with a wonderful evocation of pre-war Antwerp and wartime London.

All my life I have lied. I lied to escape, I lied to be loved, I lied for placement and power; I lied to lie. It was a way of living; lies are life’s almost-anagram.

BONUS: This version of Enid Blyton’s Noddy that Banville wrote.

OK Niall, I have to come clean. I have not read a single thing by John Banville. I don’t doubt that it’s great stuff, but I have a full box of books still unread. When I eventually get through those, I will definitely seek out some Banville. That’s a promise, because it does seem to be excellent. Might be a good while though…

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLike

pete, you might enjoy the Benjamin Black mysteries: they are an easy ‘in’ to Banville

LikeLike

OK mate, I will add them to my ever-growing list! Recommendation much appreciated, as always. Pete.

LikeLike